Ways and Means

or

On a Stroll with Mrs. Woolf

"As said before, it does not matter where one is.

However, one has to make sure to steer directly into the

impossible. Of course one has to keep the balance on

the way, though only under the single condition that the

balance is made less safe. Less and less safe."

Inger Christensen

What is the ‘impossible’, that Inger Christensen refers to? It certainly implies knowing where one is coming from – what has been possible – and the desire to look ahead and see the (tempting) void.

Actually I had caught a glimpse of where to head to, whilst working for a restorer a while ago.

Having had very little, if not to say no, experience with historic bindings it was very bewildering at first – all those early bindings with crooked angles, sloppy turn-ins, and crude headcaps! And the tooling! How could they! All over the place! But as time passed I found myself invariably drawn in. Why was that, I wondered and started to study them:

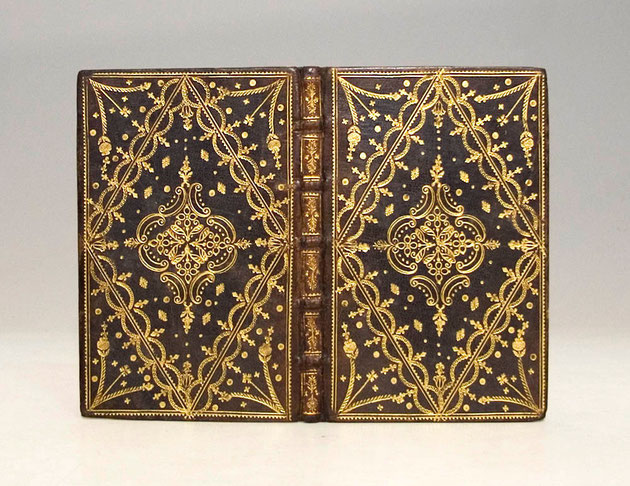

To my great surprise it was for the tooled ornaments! What appeared to be a symmetric design at first glance (Fig. 1.), was in fact, not. They were very much at ease and relaxed – playing the field, controlling their space and having a lot of character and life within them.

I had complained earlier about the ‘sloppiness’ of the workmanship, this now turned out to be an intricate and vital factor. The seemingly casual attitude towards the detailed execution added texture and depth to the ornament; it was the wind that blew the ripple onto the water and thus into life. I do not doubt for one moment that the observed liveliness is due to chance and the then-prevailing work ethos. The latter changed during the 19th century, as bookbinders became more refined and precise, and the books, at least in my eyes, turned into technical perfection, yet were very, very (!) cold indeed. Once the penny had dropped, there was no going back.

I had already started to work within tooled designs, though they had been very linear up to that point. Now I found myself breaking up the forms and shapes and was even tempted to buy a handful of old ornamental tools to work with. One can observe them popping up here and there in my designs ever since, though my aim is to come up with new visual means for them to live happily on my bindings.

Having let go of the linear way to look and approach things, I found that this opened up a whole new world to me. It was no longer about a bold statement as such, but rather addressing the relationships between the various participants and thus creating a certain sense of atmosphere. So now, when working on a binding, I read the book, take it in and put it aside. I then start doodling with tools and ink on sheets of paper that are cut to the size of the boards. This is a contemplative process, which is useful to familiarize myself with the feel of a tool in my hands and to get to know the specific shapes I might think of using. Whilst doing this I think – in an off-handed sort of way, in the back of my mind…– about the content of the book. I don’t seek to illustrate a certain scene or plot as such, for that is within the narrative world of words, which is not mine as a fine binder (otherwise I would actually write!). No, I wait until the general feel, the atmosphere of the book, crystallizes within me. Is it tense? Dithering? Happy-go-lucky?

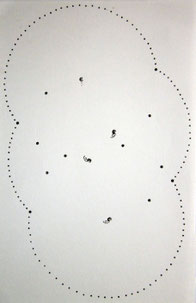

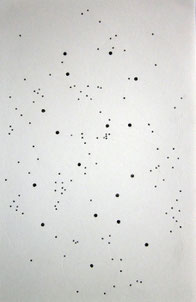

To illustrate this concept, here are three images. What you actually see is the ‘story’, i.e. a street with back light (Fig. 2), a sky (Fig. 3), and a merry-go-round (Fig. 4). What I am however trying to convey is the sense as such, without referring to the actual image (story), i.e. being blinded and possibly feeling slightly ill at ease (the street), marvelling at the cloud formation, yet being daunted by the coming rain (the sky) or having a general sense of happy foreboding (the merry-go-round). This is a rather abbreviated and abstract explanation, but I hope it will do, and quite obviously I seek to do so within the means available and in a way intrinsic to a fine binding. The above development has not been a conscious one, but I can detect it from the vantage point of hindsight. It took me about five years to stride through these gradual steps of apprehension, but then I stopped dead in my tracks as I had the distinct feeling, that I was (am) walking on a tightrope, gradually inching forward and just about to break through a wall. This might sound a little odd, coming from a bookbinder, but as the Danish author Inger Christensen puts it so well, it does not matter where or who you are.

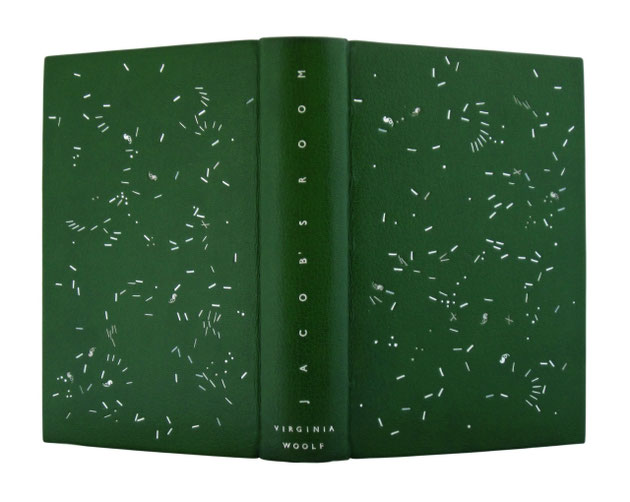

I decided that I would like to bracket this moment of change within a set project and as binding books is so closely linked to the content, I needed a strong partner in crime. I found the very person in Virginia Woolf. She remains one of the leading authors who significantly pushed the boundaries of literature into a new dimension. I am now venturing out to bind all nine of her novels in chronological order. I conveniently named the project ‘On a Stroll with Mrs. Woolf’, just to distract from the fact of how very nervous I am. With Virginia Woolf’s companionship and daring lead I hope to pull out some stops myself. So far, I have completed her first three novels The Voyage Out, Night and Day, and Jacob’s Room.

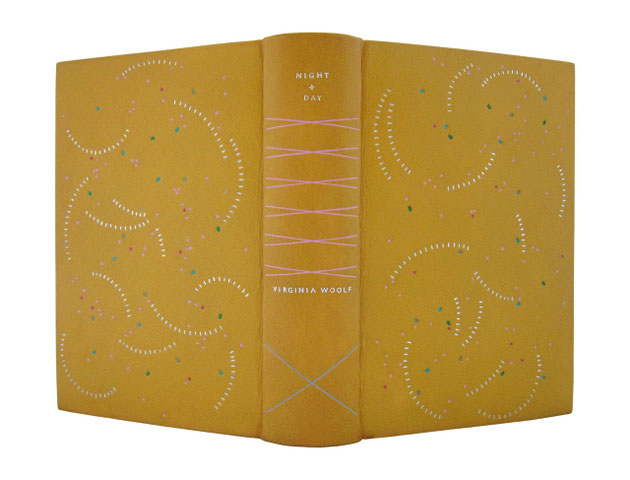

Night and Day (Fig. 5.) is Virginia Woolf's second novel. It is the very slow-paced, linear story of two young men and women looking for their place in life and falling in love with each other, though unfortunately not quite in the right constellation to make everyone happy.

Here is a selection of sheets to illustrate how my design found its way:

You can see that I started to work with circles and that I slowly became interested in the relationship between the centre, the radius and indeed the points where they overlap. Figs. 6 – 9 were interesting, but too much ‘shape’, I found this to be too strong for the floating/drifting sense I experienced while reading the novel. I added more circles and spread them out to avoid an ‘event’. I had to say my goodbye as well to the little leaf, as it now resembled too closely a gust of wind, throwing leaves into the air – again: too much action and now even evoking a definite image! (... the little leaf makes an appearance in the next design though.... Jacob's Room.) In the end I settled for highlighting segments only, with little tapered shapes. It took a long time to find the right positions for them to achieve a ‘visual’ floating by the eye of the beholder, though not of the forms as such. All in all it had taken me 51 sheets to get there (Figs. 12 – 13 are the same circle formations, which would eventually become the front board). Only then could I start to think about the colours to be used, in order to underline the lightness of atmosphere and I only jarred it slightly by adding a bold cross on the spine.

I had been familiar with most of Virginia Woolf’s work before setting out on my project. Re-reading them in chronological order, however, was an eye opener. Not only did she pursue different subjects, but indeed experimented above all with form, starting off with a linear thread of narration, then lifting the perspective to a detached onlooker’spoint of view, then shifting it yet again, penetrating minds, having them become parallel, juxtaposing these strands, and finally, interweaving poetry with prose, letting go of time and space… Phew! Scary and yet exhilarating! Her life’s work and pursuit in a nutshell! The above Night and Day was the last of her linear narratives. Following with Jacob’s Room Virginia Woolf launched herself onto the path of literary discovery. The novel tells the life of a young man, Jacob, though as in her description of his room in Cambridge, it is mostly done in his absence and he just occasionally walks through our field of vision. It is a fairly detached account, like a bird’s-eye view of his life’s map, darting down here and there and only taking in snippets.

When I worked on Jacob’s Room last summer (2012), I was aware that I now had to jump off the cliff myself. Having discovered in the previous binding, that how we look is just as important as what we actually see, it now dawned on me, that this was very likely to be the ultimate challenge for the whole project yet to unfold. In Jacob’s Room I worked with the detached ‘darting down from a bird's-eye perspective’ scenario. Have I succeeded? Possibly… but you must be the judge of that.

Quite honestly I am apprehensive to see where this project will take me in the end, but I am one hundred percent sure, that it will be somewhere quite other than from where I set out.

This is an article that was written for and published in The New Bookbinder, vol.33, 2013.

It was part of 'Ways and Means', where eight bookbinders described the coming about of a binding. Well... I took the occasion to do a survey and sweep. Much more fun.

Annette Friedrich

Annette Friedrich